The case for building credibility to keep the reader engaged.

Confession: I have never finished Gone With the Wind, neither the classic book by Pulitzer Prize winner Margaret Mitchell nor the Academy Award winning movie of the same name.

Well! I never!

Yup, sorry. I did try. I started the book several times, but each time, I put it down. DNF. Same for the movie.

Why couldn’t you make it through?

Because Scarlett O’Hara, the main character, got right up under my skin. I couldn’t admire her, I couldn’t root for her, and I couldn’t get past her conniving manipulation in every situation.

Harsh.

Obviously, I’m not Mitchell’s intended audience.

There must be a fundamental flaw in my character.

I’m the problem. (It’s me.)

All kidding aside, let’s talk about your story’s narrator. The principle of ethos applies to any point of view (POV) in fiction: first person, second person, and third person (limited, objective, and omniscient.)

What does ethos have to do with it?

Focus with me. Ethos is about credibility; it’s about truth. Ethos has related words: ethics and ethical. Think authenticity, authority, and integrity.

Your narrator isn’t required to be a nice person or a person of high moral character, but you must be able to believe them to some extent. It helps if you can:

- relate to them on some level,

- like an aspect of their character, or

- sympathize with their situation.

For example, Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins is not a particularly likable main character. She’s grumpy and taciturn. When she is put in front of the cameras, the interviewer has his work cut out for him to present her in a good light.

But Katniss wins the reader over on the very first page by her unswerving devotion and care for her innocent younger sister.

Readers also get to be inside Katniss’s head (first person), so that helps them understand her at a relatable level immediately.

However, not even first person POV can save a narrator who:

- doesn’t build good will,

- doesn’t exhibit good sense, and

- doesn’t live according to a set of values (however flawed.)

Aristotle’s pillars of character.

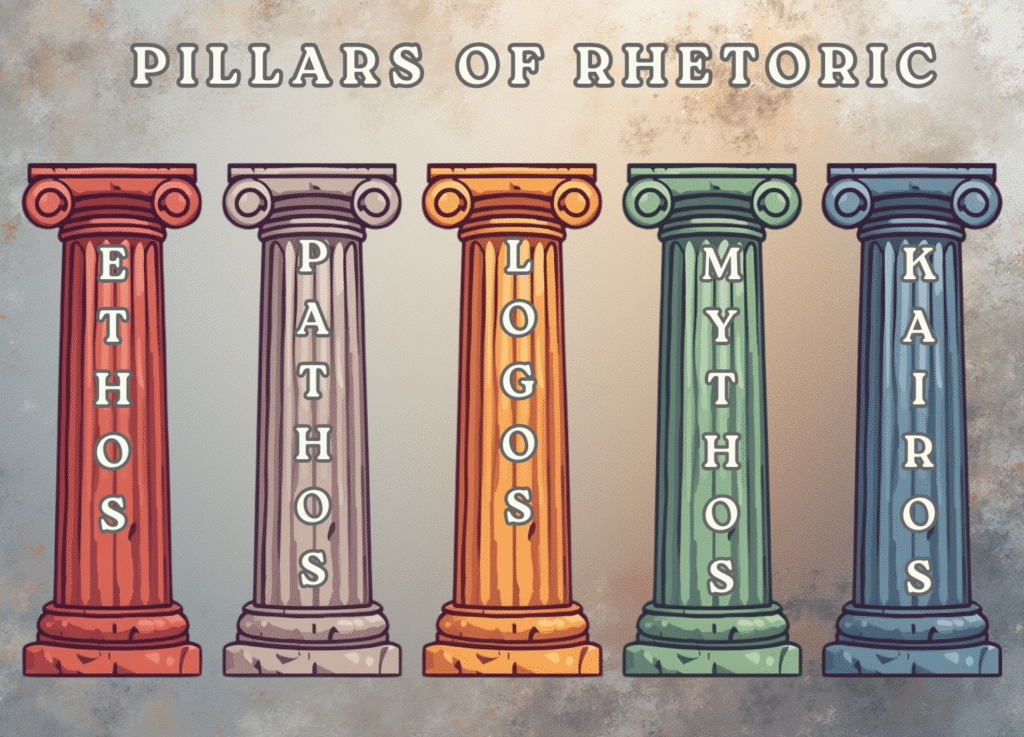

Aristotle had three pillars for character, what he called ethos, that are necessary for persuasive writing or speaking:

- good will,

- good sense, and

- good character.

For fiction authors, someone of “good character” does not necessarily mean a person of good morals but rather someone who stays true to their values. Tilt your head a bit; you can still root for a less-than-admirable person if they care about something outside themselves that you care about too.

(Don’t rely on that idea too much; nobody likes the Disney version of Cinderella’s stepmother even though she dotes on her cat, Lucifer. And this is why Scarlett couldn’t win me over; she cared about the plantation, but I had no sympathy for her motivation.)

“Good sense” is easy to understand because a character who is too stupid to live is aggravating, not endearing. If you force your main character into a stupid choice, at least let us know they know it’s stupid.

Finally, “good will” is an earned asset; your narrator needs to bank as much of it as possible before they make a withdrawal.

For example, Hank the Cowdog, in the series of the same name, is what is known as an unreliable narrator. He’s kind of stupid and makes lots of bad choices; you can’t take anything he says at face value. I mean, he’s a dog—cut him some slack—but he thinks he’s’ God’s gift to the ranch.

However, Hank’s narration is just so entertaining that the reader is willing to tolerate his lack of good sense and good character because he builds good will from the get go:

“I know I shouldn’t blame myself. I mean, a dog is only a dog. He can’t be everywhere at once. When I took this job as Head of Ranch Security, I knew that I was only flesh and blood, four legs, a tail, a couple of ears, a pretty nice kind of nose that the women really go for, two bushels of hair and another half-bushel of Mexican sandburs.” —John R. Erickson, The Original Adventures of Hank the Cowdog

For more about unreliable narrators, see Use Unreliable Narrators in Your Stories | Writing Pursuits.

Remember ethos when you choose your POV.

Choosing who tells your story is perhaps the most important decision you make when you begin writing.

And ethos has everything to do with the POV decision.

Ask yourself:

- Can your narrator or POV character tell the story to the end or must someone else finish the tale?

- Will readers believe in the POV character(s)? Will readers root for them?

- What special angle does the outside narrator or the POV character have that makes them the best choice to frame the story? Who in the story has the most to lose? What sort of credibility does the narrator have?

- Does the story need (and I mean really need) multiple points of view? If so, every narrator needs ethos and a unique voice.

- Should a POV character tell their own story (first person) or would it be better for the author to tell the story (third person limited, objective, or omniscient)?

- Is the conceit of telling a fictional story in second person worth the effort?

- Does the chosen narrator have enough ethos to engage the reader long term?

For more detailed information about choosing a point of view, see my post: Your First Chapter: Point of View | Writing Pursuits.

Get your free First Chapter Rubric here.

Additional Resources:

- Third Person Point of View: Omniscient, Limited, and Objective | Manuscript Mentoring

- Character Ethos: Three ways to make readers care about your characters | Thinking Through Our Fingers

Persuasive Fiction Series

Persuasive Fiction: Make Your Book Impossible to Put Down (Intro)